Because of the changes in the LFCS exam requirements effective Feb. 2, 2016, we are adding the necessary topics to the LFCS series published here. To prepare for this exam, your are highly encouraged to use the LFCE series as well.

One of the most important decisions while installing a Linux system is the amount of storage space to be allocated for system files, home directories, and others. If you make a mistake at that point, growing a partition that has run out of space can be burdensome and somewhat risky.

Logical Volumes Management (also known as LVM), which have become a default for the installation of most (if not all) Linux distributions, have numerous advantages over traditional partitioning management. Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of LVM is that it allows logical divisions to be resized (reduced or increased) at will without much hassle.

The structure of the LVM consists of:

- One or more entire hard disks or partitions are configured as physical volumes (PVs).

- A volume group (VG) is created using one or more physical volumes. You can think of a volume group as a single storage unit.

- Multiple logical volumes can then be created in a volume group. Each logical volume is somewhat equivalent to a traditional partition – with the advantage that it can be resized at will as we mentioned earlier.

In this article we will use three disks of 8 GB each (/dev/sdb, /dev/sdc, and /dev/sdd) to create three physical volumes. You can either create the PVs directly on top of the device, or partition it first.

Although we have chosen to go with the first method, if you decide to go with the second (as explained in Part 4 – Create Partitions and File Systems in Linux of this series) make sure to configure each partition as type 8e.

Creating Physical Volumes, Volume Groups, and Logical Volumes

To create physical volumes on top of /dev/sdb, /dev/sdc, and /dev/sdd, do:

# pvcreate /dev/sdb /dev/sdc /dev/sdd

You can list the newly created PVs with:

# pvs

and get detailed information about each PV with:

# pvdisplay /dev/sdX

(where X is b, c, or d)

If you omit /dev/sdX as parameter, you will get information about all the PVs.

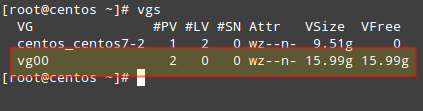

To create a volume group named vg00 using /dev/sdb and /dev/sdc (we will save /dev/sdd for later to illustrate the possibility of adding other devices to expand storage capacity when needed):

# vgcreate vg00 /dev/sdb /dev/sdc

As it was the case with physical volumes, you can also view information about this volume group by issuing:

# vgdisplay vg00

Since vg00 is formed with two 8 GB disks, it will appear as a single 16 GB drive:

When it comes to creating logical volumes, the distribution of space must take into consideration both current and future needs. It is considered good practice to name each logical volume according to its intended use.

For example, let’s create two LVs named vol_projects (10 GB) and vol_backups (remaining space), which we can use later to store project documentation and system backups, respectively.

The -n option is used to indicate a name for the LV, whereas -L sets a fixed size and -l (lowercase L) is used to indicate a percentage of the remaining space in the container VG.

# lvcreate -n vol_projects -L 10G vg00 # lvcreate -n vol_backups -l 100%FREE vg00

As before, you can view the list of LVs and basic information with:

# lvs

and detailed information with

# lvdisplay

To view information about a single LV, use lvdisplay with the VG and LV as parameters, as follows:

# lvdisplay vg00/vol_projects

In the image above we can see that the LVs were created as storage devices (refer to the LV Path line). Before each logical volume can be used, we need to create a filesystem on top of it.

We’ll use ext4 as an example here since it allows us both to increase and reduce the size of each LV (as opposed to xfs that only allows to increase the size):

# mkfs.ext4 /dev/vg00/vol_projects # mkfs.ext4 /dev/vg00/vol_backups

In the next section we will explain how to resize logical volumes and add extra physical storage space when the need arises to do so.

Resizing Logical Volumes and Extending Volume Groups

Now picture the following scenario. You are starting to run out of space in vol_backups, while you have plenty of space available in vol_projects. Due to the nature of LVM, we can easily reduce the size of the latter (say 2.5 GB) and allocate it for the former, while resizing each filesystem at the same time.

Fortunately, this is as easy as doing:

# lvreduce -L -2.5G -r /dev/vg00/vol_projects # lvextend -l +100%FREE -r /dev/vg00/vol_backups

It is important to include the minus (-) or plus (+) signs while resizing a logical volume. Otherwise, you’re setting a fixed size for the LV instead of resizing it.

It can happen that you arrive at a point when resizing logical volumes cannot solve your storage needs anymore and you need to buy an extra storage device. Keeping it simple, you will need another disk. We are going to simulate this situation by adding the remaining PV from our initial setup (/dev/sdd).

To add /dev/sdd to vg00, do

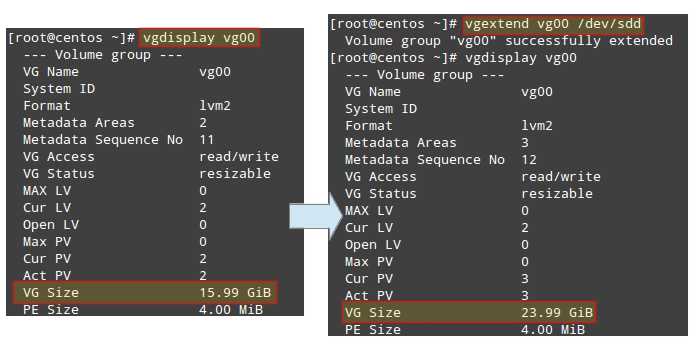

# vgextend vg00 /dev/sdd

If you run vgdisplay vg00 before and after the previous command, you will see the increase in the size of the VG:

# vgdisplay vg00

Now you can use the newly added space to resize the existing LVs according to your needs, or to create additional ones as needed.

Mounting Logical Volumes on Boot and on Demand

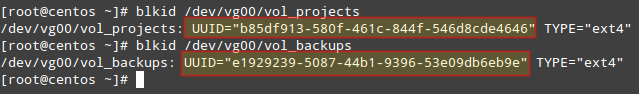

Of course there would be no point in creating logical volumes if we are not going to actually use them! To better identify a logical volume we will need to find out what its UUID (a non-changing attribute that uniquely identifies a formatted storage device) is.

To do that, use blkid followed by the path to each device:

# blkid /dev/vg00/vol_projects # blkid /dev/vg00/vol_backups

Create mount points for each LV:

# mkdir /home/projects # mkdir /home/backups

and insert the corresponding entries in /etc/fstab (make sure to use the UUIDs obtained before):

UUID=b85df913-580f-461c-844f-546d8cde4646 /home/projects ext4 defaults 0 0 UUID=e1929239-5087-44b1-9396-53e09db6eb9e /home/backups ext4 defaults 0 0

Then save the changes and mount the LVs:

# mount -a # mount | grep home

When it comes to actually using the LVs, you will need to assign proper ugo+rwx permissions as explained in Part 8 – Manage Users and Groups in Linux of this series.

Summary

In this article we have introduced Logical Volume Management, a versatile tool to manage storage devices that provides scalability. When combined with RAID (which we explained in Part 6 – Create and Manage RAID in Linux of this series), you can enjoy not only scalability (provided by LVM) but also redundancy (offered by RAID).

In this type of setup, you will typically find LVM on top of RAID, that is, configure RAID first and then configure LVM on top of it.

If you have questions about this article, or suggestions to improve it, feel free to reach us using the comment form below.

when you created mount points for each LVs, /home/projects, /home.backups, how they got their mounting directory, ? just with mount -a command?

Mount points are set in /etc/fstab:

UUID=b85df913-580f-461c-844f-546d8cde4646 /home/projects ext4 defaults 0 0

UUID=e1929239-5087-44b1-9396-53e09db6eb9e /home/backups ext4 defaults 0 0

As UUIDs are unique, it’s the best way to identify each volume.

Then, ‘mount -a’ reads /etc/fstab and mounts all the volumes configured in it

Another option is to set a LABEL for the logical volume as explained here: https://www.tecmint.com/change-modify-linux-disk-partition-label-names/

Is there any scenario where someone will have two volume group? does it add any significance?

@Alexandre,

Good catch!

@Ravi,

Please replace the second appearance of Fig. 5 with Fig. 6. Alexandre is right. Please let me know if you still have this image or if you want me to resend it.

@Alexandra,

That was really a good catch!

@Gabriel,

That was my mistake, corrected the image..

You ‘ve used this screenshot twice ( Find Logical Volume UUID ) . Is it normal ?